The Scale of Everything

April 15, 2019

UMD English professor named Guggenheim and American Council of Learned Societies fellow.

By Lorraine Graham

When the astronomer and mathematician Nicolaus Copernicus published "On the Revolutions of the Celestial Spheres" in 1543, people were shocked by his claim that the earth revolved around the sun. His theory also raised a question of scale. People wondered, how can we now understand our tiny place in a potentially infinite universe?

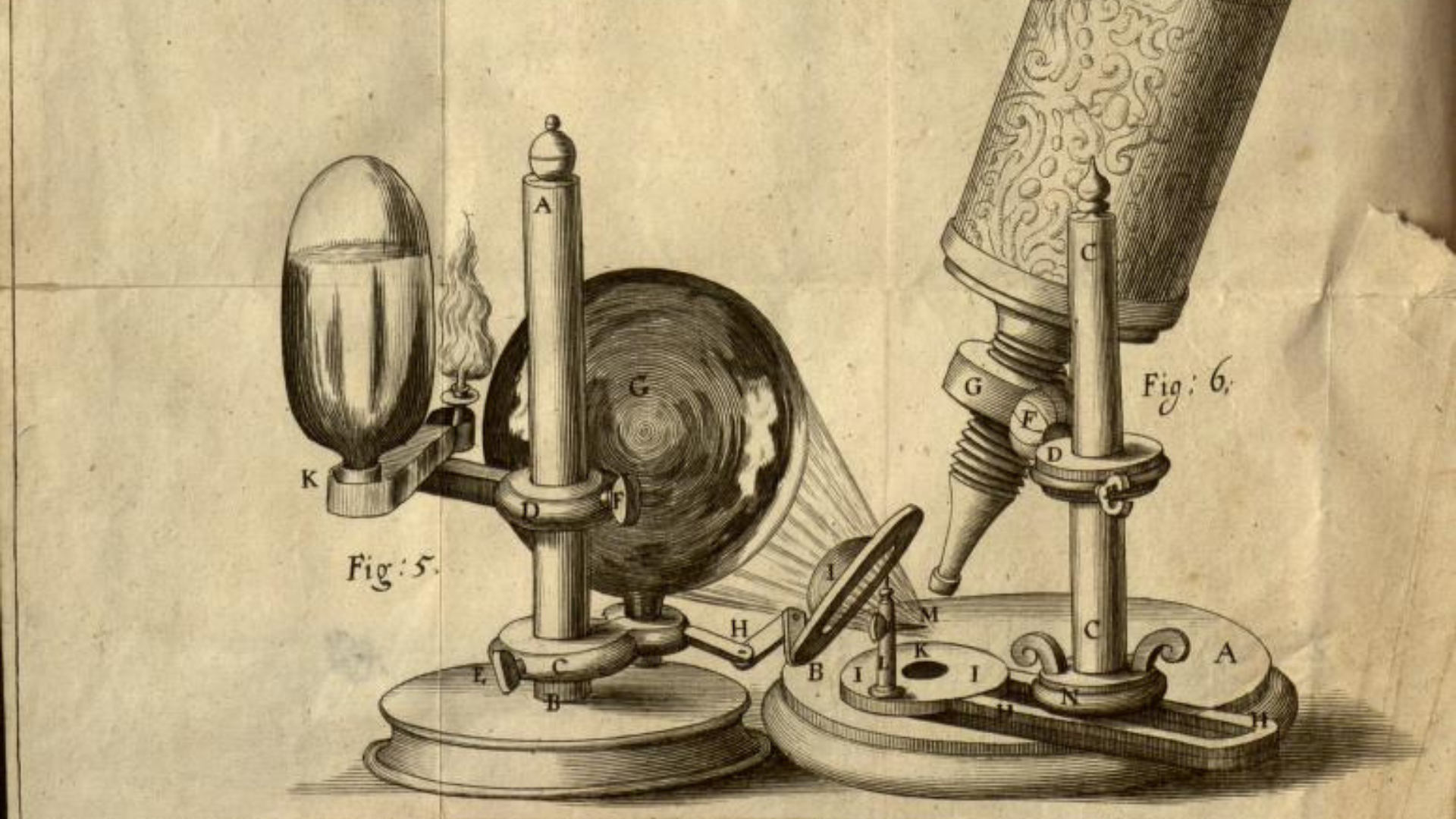

Gerard Passannante, associate professor of English, recently received both a Guggenheim Fellowship and an American Council of Learned Societies (ACLS) Fellowship to support his research on how contemporary ideas about scale, or the relative size or extent of something, have roots in ancient and early modern arguments about the order of the universe. In his project, "God is in the Detail," Passannante will explore a variety of literary and philosophical discussions of scale—for example, ancient arguments about cosmic order, Hamlet’s musings on infinity, the discovery of calculus and the bodies of insects as seen through a microscope.

"It's about the history of the strategies we have for confirming that the world is secure and orderly—that 'everything’s fine'—in spite of what experience might say to the contrary," says Passannante. "It’s about finding evidence of order in the very smallest of things."

The phrase "God is in the detail" suggests that the divine is evident in even the smallest of things. Passannante chose it as the title of his project because it speaks to how questions of scale are caught up in questions about the order of the universe. He sees similar patterns emerging in contemporary thought, especially discussions of global warming.

"We live in a moment of profound ecological crisis, but we are dismayingly good at reassuring ourselves by finding order in small things," he said. "I want to create a historical lens through which to see our own practices of interpretation in another light."

As an early modern specialist, Passannante studies European literature and culture from the 14th to the 18th century—from the verses of the poet Petrarch to the philosophy of Immanuel Kant. He is especially interested in how ideas travel. Passannante's first book, "The Lucretian Renaissance:Philology and the Afterlife of Tradition," examined how the ideas of the first century B.C. Roman poet and philosopher Lucretius were transmitted and received in the early modern period.

The inspiration for Passannante's Guggenheim and ACLS project came while writing his recently published second book, "Catastrophizing: Materialism and the Making of Disaster," which traces the literary and philosophical history of catastrophizing, or imagining the worst. The book touches on everything from Leonardo da Vinci's musings on the destructive forces of nature to the doomsday predictions of Renaissance astrologers.

"I was struck by the way ideas about scale were connected to ideas about the nature of God," he says. "I wanted to understand how and why people argued historically that God is present in even the smallest of things and how they translated this claim into a feeling."

Passannante, who joined the department of English in 2007, says the project also was inspired by teaching a University Honors College seminar on “How to Think Like Leonardo, Montaigne, and Shakespeare.”

"One thing that those writers teach us, albeit in very different ways, is how to think between scales," he says. "That is, how to learn from startling shifts in perspective."

Established in 1925, the Guggenheim Memorial foundation has awarded more than $360 million to over 18,000 people. Past winners from the College of Arts and Sciences include poet and essayist Reginald Dwayne Betts ’09, English (2018) and historian Ira Berlin (2010).

Image. Robert Hooke’s microscope. "Micrographia,"1665. Robert Hooke. Via the Biodiversity Heritage Library. Robert Hooke was an English natural philosopher, and one of the figures who inspired Passannante's project.